By DB Sikes

Before checklists were printed, they were scribbled.

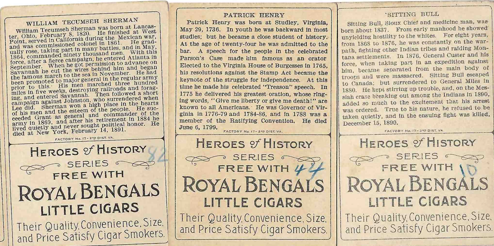

In the earliest days of tobacco card collecting—around 1910 to 1911—there were no master lists, no official card guides, and certainly no web forums to ask what you were missing. Kids and collectors alike had only one reliable reference: the backs of their own cards.

That’s why, among Heroes of History T68 cards, you’ll sometimes find handwritten numbers—penciled or inked in the corners, written vertically along the edges, or faintly scrawled across the factory-stamped panel. These weren’t accidents. They were homemade checklists.

Why Collectors Wrote on the Backs

Without an official series guide, the only way to keep track of the 50 or 100 cards in a set was to create your own reference system. For many early collectors, that meant writing directly on the card itself.

Some numbered every card as they acquired it—1, 2, 3, all the way to 100. Others only marked their duplicates to prep for trade. Pencil was most common, but some used fountain pen, indelible blue, or even wax crayon. The writing could be tidy and deliberate, or crooked and fading with age.

In a few rare cases, backs were converted into full grid systems or cross-check lists. But more often, a small “✓,” a boxed number, or a sequence scribbled in the margin served as a quiet declaration: this one’s in the set.

These weren’t flaws. They were tools—personal indexing systems from a time before card sleeves, spreadsheets, or Beckett price guides.

A Fictional Story: Elijah Carter and the Card Marked “44”

Among a small lot of T68 cards purchased in a batch, a well-worn Patrick Henry card turned up—its back marked clearly in graphite with the number “44.” Several other cards in the lot bore similar numbering.

While the original owner remains unknown, the following fictional account pays tribute to the kind of early hobbyist who may have started one of the first checklist systems, not with a catalog, but with a pencil stub and a love of history.

In the fall of 1911, Elijah Carter was a young schoolteacher in Danville, Virginia. He had a quiet fascination with the miniature portraits that came tucked into Royal Bengals cigar packs—cards featuring Revolutionary heroes, tribal leaders, and war generals.

Though he didn’t smoke, Elijah began collecting the cards, trading with students and neighbors, sometimes even slipping one into a book as a teaching aid. With no printed guide, he numbered them as he went. The Patrick Henry card, received from a fellow teacher who smoked Royal Bengals, was the 44th in his set. He wrote it carefully on the back—just a number, but a number with purpose.

He stored them in a small wooden cigar box beneath his desk. Over time, he logged dozens of names in a repurposed attendance ledger, checking off who he had, circling those he still hoped to find. It was his quiet pursuit—history, structure, and a touch of childhood joy in a grown-up world.

Though Elijah’s story is fictional, cards like his—with faint pencil marks and handwritten numbers—do exist. And each mark may carry with it the echo of someone who once cared enough to track their collection the only way they could: by writing it down.

Real-World Examples from the Field

Collectors today still uncover T68s with handwritten notations—sometimes partially erased, other times still bold and legible. These include:

- Sequential numbers (1–100)

- Duplicate markings (“x2” or “dup”)

- Checkmarks or dots

- Initials or trade notations

- Crossed-out backs from reorganized sets

In many cases, the markings help piece together early collecting habits—particularly when multiple cards from the same original set appear in one lot. These markings show how meaningful collecting was to people long before hobby shops or archival protection.

A Glimpse into the First Hobbyists

Not all of these marks were made by children. Some show a careful, practiced hand—perhaps a merchant, schoolteacher, or cigar store clerk cataloging a full display. Others clearly reflect youthful enthusiasm: crooked numbers, inkblots, or back-to-front scribbles.

But whether adult or adolescent, each mark reveals intentionality. These weren’t idle doodles. They were quiet acts of cataloging—the very beginning of organized collecting as we know it today.

Before Beckett, Before Topps…

The next time you find a T68 with a penciled number or a faint “✓” on the back, think twice before calling it a flaw.

It may be one of the very first checklist systems in the hobby—built not with software, but with memory, repetition, and a stub of pencil from a desk drawer in 1911.

These marks are the fingerprints of the earliest collectors. They’re part of the story, not an error to erase.

Leave a Reply